108 Red Stitches continues its week long tribute to African American ballplayers in honor of Martin Luther King, Jr.

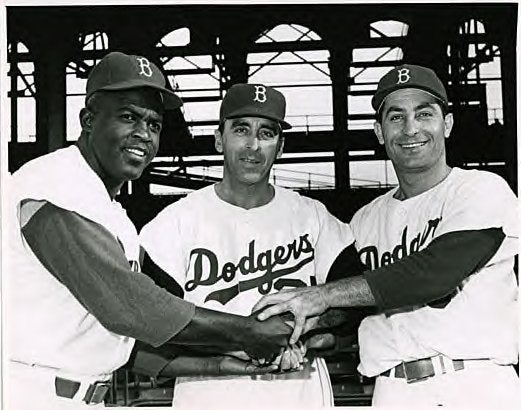

Joe Black, a right handed pitcher for the Dodgers during the fifties, was one of Robinson’s roommates on road trips. He and Robinson became close and in an interview with Robinson biographer Maurey Allen, Black said that “Jackie developed this internal defense system, this thick skin, and he just didn’t let it bother him. Sure he was dying inside, but he felt the real answer was just playing well and beating the other guys” (Allen; 189). Jimmy Cannon of the New York Post gave Jackie Robinson the nickname of “the loneliest man I have seen in sports” (Rampersad; 172).

roommates on road trips. He and Robinson became close and in an interview with Robinson biographer Maurey Allen, Black said that “Jackie developed this internal defense system, this thick skin, and he just didn’t let it bother him. Sure he was dying inside, but he felt the real answer was just playing well and beating the other guys” (Allen; 189). Jimmy Cannon of the New York Post gave Jackie Robinson the nickname of “the loneliest man I have seen in sports” (Rampersad; 172).

The incident between Robinson and the Phillies opened a Pandora’s box for those who wished ill of Robinson. With the press focusing on the events of the three game series, those who had ripped Robinson quietly now had the opportunity to let fly their bigotry and hatred;

“The escalation of public disclosures about the ridicule and hatred heaped on Robinson by the Phillies unearthed more snakes. Hate mail increased. Death threats were plentiful. Scribbled letters came in daily, with vulgarities” (Allen; 132).

Had the press kept the problem quiet, (fans who attended the game knew little of the verbal bashing Robinson received from Chapman and his Phillies) the hate mail and death threats might have never happened, or at least have been put off for a time.

Robinson would later write that this experience almost ended his career. He believed he didn’t deserve such treatment and wrote;

“I felt tortured and I tried just to play ball and ignore the insults. [...] But it was really getting to me. What did the Phillies want from me? What, indeed, did Mr. Rickey expect of me? I was, after all, a human being.For one wild and rage-crazed minute I thought; To hell with Mr. Rickey’s noble experiment. To hell with the image of the patient black freak I was supposed to create. I could thrown down my bat, stride over to that Phillies dugout, grab one of those white sons of bitches and smash his teeth in with my despised black fist. Then I could walk away from it all.” (Rampersad; 172-73).

Robinson’s building frustration began to poison his relationships with those that surrounded him. Eventually, the Dodger began to burn bridges with the press, both black and white. Their responses further frustrated a man who just wanted to play the game, nothing more. Wendell Smith had shown that, in his column “Sports Beat, the journalist’s relationship with Robinson was worsening and accused Robinson of showing signs of ingratitude;

“This, it seems, is time for someone to remind Mr. Robinson that the press has been especially fair to him throughout his career. Were it not for the press, Robinson would be ‘just another athlete’ insofar as the public concerned. If it had not been for the press-the sympathetic press-Mr. Robinson would have

probably still been tramping around the country with Negro teams, living under what he has called ‘intolerable conditions’. [...] Mr. Robinson’s memory, as it seems, is getting shorter and shorter. That is especially true in the case of the many newspapermen

who have befriended him throughout his career” (Rampersad; 206-7).

Sam Lacy, one of Robinson’s original ardent supporters, began to attack him. In attempts to correct Jackie, Lacy wrote in the Baltimore Afro-American;

correct Jackie, Lacy wrote in the Baltimore Afro-American;

“In his (Joe Louis) at the top of boxing he has NEVER had to deny having made a statement, he has NEVER criticized the people who gave him his chance, and he has NEVER blamed someone else for anything that happened” (Rampersad; 207).

Lacy wanted Robinson to remember where he came from and to watch his mouth. Becoming a the press’ target would only further incense Robinson, and lead to more heated confrontations between the two. Luckily, Robinson found an ally in a familiar place.

To be continued.

Baseball's Great Experiment, Jackie Robinson: Part IV

Search

Archives

-

▼

2008

(191)

-

▼

January

(28)

- Superbowl MLB: Part II

- Superbowl MLB: Part I

- Mets Acquire Santana, Hope He Isn't the New Pavano

- Huge Upgrade in Philly

- Trade Between O's and Space Needles Imminent

- Baseball Roundup: 1/27/08

- 108 Red Stitches Mailbag

- 2K Sports: MLB 2K8 Release Date Confirmed

- Baseball's Bad Boys Are at it Again

- Baseball's Great Experiment, Jackie Robinson: Part V

- Baseball's Great Experiment, Jackie Robinson: Part IV

- Baseball's Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson, Part...

- Baseball's Great Experiment, Jackie Robinson: Part II

- Baseball's Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson, Part I

- Baseball Roundup: 1/17/08

- One Tejada Lied While Another One Died

- Patiently Waiting: MLB 2K8

- Baseball Wrap Up: 1/13/08

- Playing God: On the Diamond

- Goose Calls Heard in Hall of Fame

- Mitchell Report Fallout Continues

- Baseball Wrap Up: 1/7/07

- Roger Clemens on "60 Minutes"

- Free Agent "No-Mo"

- A's Re-tooling, Fan Favorite Dealt

- All's Quiet on the Diamond Front

- Flashback, July 31, 2001

- New Year's Resolutions

-

▼

January

(28)

0 Comments Received

Post a Comment